Cleansing of the Temple

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

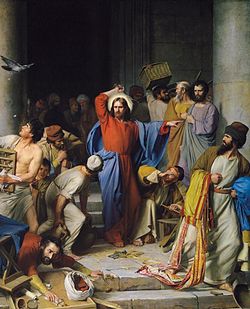

The narrative of Jesus and the Money Changers, commonly referred to as the Cleansing of the Temple, occurs in all four Gospels in the New Testament. It occurs near the end of the Synoptic Gospels (at Mark 11:15–19, 11:27–33, Matthew 21:12–17, 21:23–27 and Luke 19:45–48, 20:1–8) and near the start in the Gospel of John (at John 2:12–25). As a result some biblical scholars think there may have been two such incidents.

Contents |

Description

In this episode, Jesus is stated to have visited the Temple in Jerusalem, Herod's Temple, at which the courtyard is described as being filled with livestock and the tables of the money changers, who changed the standard Greek and Roman money for Jewish and Tyrian money, which were the only coinage that could be used in Temple ceremonies. Creating a whip from some cords, "he drove them all out of the temple, with the sheep and the oxen, and poured out the changers' money and overturned the tables. But he said to those who sold doves, "Get these out of here! Do not make My Father's house a house of merchandise!"[Jn 2:13-16]

And Jesus went into the temple of God, and cast out all them that sold and bought in the temple, and overthrew the tables of the moneychangers, and the seats of them that sold doves, And said unto them, It is written, My house shall be called the house of prayer; but ye have made it a den of thieves.

In John, this is the first of the three times that Jesus goes to Jerusalem for the Passover, and John says that during the Passover Feast there were (unspecified) miraculous signs performed by Jesus, which caused people to believe in his name, but that he would not entrust himself to them, for he knew all men. Some scholars have argued that John may have included this latter statement, about knowing all men, in order to portray Jesus as possessing a knowledge of people's hearts and minds (Brown et al. 955), and hence have attributes that would be expected of God.

This event satisfies the criterion of multiple attestation, and scholars of the historical Jesus generally credit this event as genuine and associate it with Jesus' arrest and crucifixion and as one of the first events separating Christianity from Judaism. It is believed the money changers and merchants were located south and south-west of the Temple Mount, an area excavated by archaeologist Prof. Benjamin Mazar shortly after the reunification of Jerusalem in 1967.

Jerusalem historian Dan Mazar reported in a series of articles in the Jerusalem Christian Review on the archaeological discoveries made at this location by his grandfather, Prof. Mazar, which included the finding of a first century vessel with the Hebrew word "Korban", meaning sacrifice(s), and it is believed that in this vessel the merchants stored the sacrifices sold at the Temple Court. Other discoveries at this location included the first century stairs of ascent, where Jesus and his disciples preached , as well as the mikvaot (ritual baths) used by Jewish pilgrims.

Narrative details

Jesus' criticism

According to the synoptics, Jesus targeted specifically the money changers and the dove sellers, explaining his actions by quoting from the Book of Isaiah and the Book of Jeremiah:

- My house will be called a house of prayer for all nations.—Isaiah 56:7

and

- But you have made it a den of thieves—Jeremiah 7:11

The quote from Isaiah comes from a section which instructs that all who obey God's will, whether Jewish or not, are to be allowed into the Temple so that they can pray, and therefore converse with God. The loud market-like atmosphere of money changers and livestock often seems to modern readers to be at odds with the Temple being a place of quiet prayer. However, this interpretation may reflect anachronistic perceptions of ancient worship—which often involved the sacrificial slaughter of animals—and the manner in which understandings of pre-Christian ritualistic practices intersect with modern notions of contemplative worship. Further, from a Judaic cultural perspective, Jews would have certainly utilized money changers, yet the currency exchange would have been primarily accessed by non-Hebrew travelers changing foreign coins.

The area in question was almost certainly the Court of the Gentiles, a location in the massive Temple complex setup specifically for the purpose of purchasing sacrificial animals and—out of necessity—a place where Jewish pilgrims could exchange their foreign coinage for the appropriate local currency.

The reference to den of thieves may be a reference to inflated pricing or more sinister forms of using a religious cult to exploit the poor. Or, simply to exaggerate the dishonesty of the traders. In Mark 12:40 and Luke 20:47 Jesus again accuses the Temple authorities of thieving and this time names poor widows as their victims going on to provide evidence of this in Mark 12:42 and Luke 21:2. Dove sellers were selling doves that were sacrificed by the poor who could not afford grander sacrifices and specifically by women. According to Mark 11:16, Jesus then put an embargo on people carrying any merchandise through the temple—a sanction that would have disrupted all commerce.

The synoptics then state that those in the crowd were in awe of Jesus, which concerned "the chief priests and the teachers of the law." Luke and Mark say these Temple leaders were so concerned that they began to plot against Jesus' life, to which Luke adds that the crowd were so in awe with Jesus that no-one could be found to assassinate him.

Matthew says the Temple leaders questioned Jesus if he was aware the children were shouting Hosanna to the Son of David, and Jesus responded by accepting the worship of the children as valid by quoting ...from the lips of children and infants you have ordained praise from the Book of Psalms (Psalm 8:2).

The Gospel of John presents a quite different exchange. Jesus is described as angrily criticising the occupants of the temple for turning it into a market. At some point (either after or during the incident) the disciples are described as remembering the quotation zeal for your house consumes me (Psalms 69:9). The word in Greek is ζηλος/zelos from which Zealots is derived.

[edit] Jesus' authority

The synoptics and John state that Jesus left the temple after the incident with the money changers, but returned to the Temple courts a day later (though Luke is unspecific how many days had passed), and begins teaching.

The priests, teachers, elders, Pharisees and Herodians are described as coming up to Jesus, and questioning his authority to do the things that he is doing; John makes it clear that they are referring to his actions in scattering the livestock and overturning the tables of the moneychangers, but the synoptics imply that it is in reference to his teaching. The synoptics recount that Jesus called into question their own authority or allegiances.

First he asks his opponents to say whether John the Baptist's authority to baptise was divine or human. They do not believe John had divine authority, and so wanting to answer that he was just baptizing as a man—but this would run into conflict with the crowd, who believe in John's divine authority. Since the Temple authorities care so much about what the crowd thinks, this leaves them unable to answer truthfully, and so they are forced to claim that they don't know, exposing their divided loyalties and making them look incompetent. Jesus responds that in consequence he won't tell them what his authority is.

A second time when asked about Roman taxes, Jesus doesn't produce a Roman coin but asks his opponents to. American Standard Version: "Shall we give, or shall we not give? But he, knowing their hypocrisy, said unto them, Why make ye trial of me? bring me a denarius, that I may see it."[Mk. 12:15] They are able to produce one with an image of Caesar. He responds that those who are (or that which is) Caesar's should be given to Caesar and those who are (or that which is) God's should be given to God. See also Render unto Caesar....

The Gospel of John, which throughout presents John the Baptist as having no independent following, instead gives a quite different challenge and resolution of Jesus' authority. John recounts that Jesus was asked to perform a miraculous sign, but Jesus replies destroy this temple, and I shall raise it again in three days. The Gospel of John explains that Jesus had meant his body, and that this is what his disciples came to believe after his resurrection.

To most scholars this shows a clear split between Judaism and the community surrounding the Gospel of John, as the suggestion that the people should destroy the temple would have been highly offensive to the Jewish people. It is also notable that John refers to the people as the Jews, distancing both the intended audience of his Gospel, and Jesus, from any Jewish roots.

Interpretations

The differences between John and the synoptics, particularly the fact that the synoptics have the incident at the opposite end of the narrative, have led some Christian apologists to insist that Jesus must have fought with the money changers twice, once near the beginning and once near the end of his ministry. More critical scholars are inclined to instead suggest that there was only the one episode, but that John relocated the story, perhaps to imply that Jesus' arrest was for the raising of Lazarus (John 11), not the incident in the Temple (Brown et al. 954).

Scholars of the historical-critical method see this event as satisfying the criteron of multiple attestation. Unlike certain other events in the Gospels, this event appears in all of them. The event is also consistent with Jesus being arrested and crucified by Pilate, another part of the Gospel narrative generally considered to be historical.

The Temple incident, however, doesn't satisfy the criterion of dissimilarity. That is, Early Christians may have had a motive to invent this scene. Paula Fredriksen, a scholar of the historical Jesus, argues on this basis that it never happened.

Scholars give a variety of dates for the writing of the Gospels but there is consensus that they were written around the time of the Destruction of the Temple, with possibly Mark the earliest being written before the Temple's destruction and the others following it. In Mark, the historical context could inform discourse about whether Jesus' disciples were to defend the Temple as the center of Jewish religious life, or abandon it while maintaining their faith in God.

- When you see the desolating sacrilege set up where it ought not to be (let the reader understand), then those in Judea must flee to the mountains.v—Mark 13:14

By the time most scholars think that John was written (c. 95–110 AD), defending the temple was a moot point because it was long gone, and so John can be understood to have been deliberately trying to portray Early Christianity itself as a replacement—a new Temple, see also New Covenant, New Commandment, New Jerusalem, and Supersessionism. The pre-Temple-destruction community of Essenes, associated with the Dead Sea scrolls, also speaks of the community itself as a temple, and the concept was evidently one that had been circulating (Brown et al. 954).

According to a Jewish Encyclopedia article,

- This would appear to have been on the first day of the week and on the 10th of Nisan, when, according to the Law, it was necessary that the paschal lamb should be purchased. It is therefore probable that the entry into Jerusalem was for this purpose. In making the purchase of the lamb a dispute appears to have arisen between Jesus' followers and the money-changers who arranged for such purchases; and the latter were, at any rate for that day, driven from the Temple precincts. It would appear from Talmudic references that this action had no lasting effect, if any, for Simon ben Gamaliel found much the same state of affairs much later (Ker. i. 7) and effected some reforms. The act drew public attention to Jesus, who during the next few days was asked to define his position toward the conflicting parties in Jerusalem. It seemed especially to attack the emoluments of the priestly class, which accordingly asked him to declare by what authority he had interfered with the sacrosanct arrangements of the Temple. In a somewhat enigmatic reply he placed his own claims on a level with those of John the Baptist—in other words, he based them on popular support.

Jesus may have been calling for an end to the entire cultic system—symbolised by his overturning of the stations used by lepers[Mk. 1:44]) and women.[5:25–34] They represented the concrete mechanisms of oppression within a political economy that doubly exploited the poor and unclean. Not only were they considered second class citizens, but the cult obliged them to make reparation, through sacrifices, for their inferior status—from which the marketers profited. Jesus utterly repudiates the temple state, which is to say the entire socio-symbolic order of Second Temple Judaism. His objections have been consistently based upon one criterion: the system's exploitation of the poor. The "mountain" must be "moved," not restored.