Ministry of Jesus

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

According to the Canonical Gospels, the ministry of Jesus began when Jesus was around 30 years old, and lasted a period of 1–3 years. In the biblical narrative, Jesus' method of teaching involved parables, metaphor, allegory, sayings, proverbs, and a small number of direct sermons. This was the first coming of Jesus; as most Christian denominations believe in a Second Coming when Jesus will return to the earth to fulfill aspects of Messianic prophecy, such as the general Resurrection of the Dead, the Last Judgment of the dead and the living and the full establishment of the Kingdom of God on earth (also called the "Reign of God"), including the Messianic Age.

Contents[hide] |

[edit] The start of Jesus' ministry

[edit] From Nazareth to Capernaum

Some time after having been baptized by John in the Jordan river and tempted by Satan in the Judean desert, Jesus is described as leaving his hometown, Nazareth. While Matthew does not explain why Jesus did this, both he and Mark mention that John the Baptist was arrested by Herod Antipas at this time. Luke gives a different circumstance, stating that Jesus left when the people of Nazareth rejected him. The texts do not recount what occurred between Jesus being tempted and John being arrested. France[1] argues that it was the flight from Nazareth which resulted in Jesus carrying out a ministry based on itinerant preaching, which France[1] sees as being quite different to the ministry which John the Baptist had carried out.

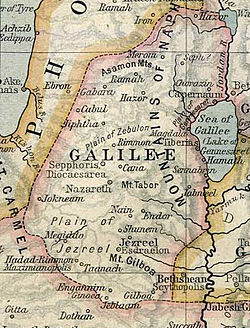

Curiously, the passage describing Jesus leaving Nazareth, both in Luke and Matthew, uses the spelling Nazara for Nazareth, which between them are the only places in the Bible that Nazareth is spelled this way. After leaving Nazareth, Jesus goes to Capernaum, a sizeable town on the northwest shore of the Sea of Galilee, located in the region that Jewish sources considered to be Naphtali, but near the region considered to be Zebulun.

Although the town is mentioned nowhere in the Old Testament, it does feature in all the Gospels, and is likely to have been a new town that arose at some point during Roman control of the region.[2] Matthew is the only source that has Jesus actually living in the town, while the other Gospels only have him preaching and meeting disciples there. To explain this, those who view the Gospels as harmonious with each other, such as France,[1] feel that the town was less a home and more a base of operations to which Jesus and his disciples would occasionally return. Gundry rejects this view, since to him dwelt unambiguously means that Jesus set up house in the town, and Gundry considers that this was a deliberate embellishment by Matthew to make it easier to find a prophecy to justify the move.

Matthew does not mention why Jesus moved, though historically the town was prosperous, mainly due to its location on a large lake (the Sea of Galilee) and simultaneously a location on the Via Maris, the Damascus to Egypt trade route. France[1] feels that Jesus moved there as such a prosperous community offered more opportunities to preach, while Albright and Mann propose that Jesus moved there because he was already friends with his disciples prior to them becoming disciples, and he wanted to live with his friends, who lived in Capernaum. According to Matthew, when he spied certain fishermen in the region, Jesus recruited them as his disciples—Simon, John, Andrew, and James.

[edit] Capernaum as prophecy

Matthew justifies Jesus' move to Capernaum by claiming that it fulfilled a prophecy. The prophecy Matthew quotes is from Isaiah 9:1-2: ...in the former time the Lord brought into contempt the land of Zebulun and the land of Naphtali, but in the latter time He will make it glorious.... Matthew has considerably abridged it, turning it into little more than a geographic list of places. In Isaiah, the passage describes how Assyrian invaders are increasingly aggressive as they progress toward the sea, while Matthew has re-interpreted the description as a prophecy stating that Jesus would progress (without any hint of becoming more aggressive) toward Galilee.

While Matthew uses the Septuagint rendering of Isaiah, in the Masoretic text it refers to the region of the gentiles rather than Galilee of the nations, and it is likely that the presence of the word Galilee in the Septuagint is a translation error—the Hebrew word for region is galil which can easily be corrupted to Galilee. Gundry feels that instead of Isaiah referring to Assyrians progressing to the Mediterranean, Matthew is trying to rewrite the statement so that it refers to the Sea of Galilee. Schweitzer considers it odd that the phrase beyond the Jordan was not among those cut in Matthew, as it makes clear that the author of the passage is writing from east of the Jordan, and the geography does not work with the sea in question being the Sea of Galilee, which is on the Jordan, not beyond it.

The quote goes on to prophesy that after the dark period of Assyrian dominance, a light would shine, and Matthew words his quote to imply that Jesus would be this light. Carter, who has advanced the thesis that much of Matthew is intended to prophesy the imminent destruction of the Roman Empire, sees this quote as a deliberate allegory, with the Assyrians representing the then current domination of the region by Rome. The wording of this part of the quote isn't consistent with any single known ancient manuscript, but several parts of it match different versions of the Septuagint, and three versions in particular. It was long thought to be combined from differing versions, but it could also be taken from a now lost version of the Septuagint, although Matthew differs by placing the text in the past tense, to fit better with his narrative. Also, while the Septuagint states that a light would shine, Matthew states that it would dawn, an important difference that makes it refer to the appearance of a messiah, rather than the continuous behaviour of God.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Shedinger[3] rejects the traditional view that this quote is merely a corruption of Isaiah, instead feeling that, in the original version of Matthew, the text was derived both from Isaiah 9:1-2 and Psalm 107:10. Shedinger alleges that later translators didn't realise that there was a second reference to the Psalms, and so altered the verse to make it conform more to Isaiah.[3]

[edit] Preaching, teaching, and healing

| Major events in Jesus' life from the Gospels |

|---|

|

Matthew identifies Jesus as preaching the same message that John the Baptist had delivered prior to Jesus being baptised by John, namely repent, for the kingdom of heaven is near, which Matthew refers to as the good news of the kingdom—a phrase from which the term gospel derives (gospel is derived from the Old English for good news)—and then goes on to preach, teach, and heal, throughout Galilee. Matthew depicts him teaching in synagogues, unlike the other gospels, which neither make a clear distinction between teaching and preaching, nor connect Jesus so strongly to Pharisaic behaviour. Being permitted to speak in a synagogue is generally an indication that an individual was a respected figure, and could also speak Hebrew, and by placing Jesus in synagogues, Matthew implies that these attributes are ones applying to Jesus.

Matthew describes Jesus as carrying out healing in a far less metaphorical way than Mark describes it, specifically Matthew presents it as quite literal healing of all the sickness and disease. Matthew doesn't indicate, however, whether there is anything miraculous about that, or if it just indicates that Jesus had a good knowledge of medicine and herbology, a knowledge many religious people of the time were expected to hold, though many Christians, particularly fundamentalists, view it as miracle not purely medicine. This healing came to the attention of people in the nearby region, if Matthew is to be believed, and they brought their sick and ill people to him, specifically those who suffered Torment (severe pain), paralysis, seizure (referred to as epilepsy, since at that time epilepsy was a more general term than it is now), and demonic possession. In most ancient manuscripts this region is named as Syria, a Roman Province that covered a very large area, but one late manuscript names it as Synoria, making Matthew's claim more credible, as fame in a small region nearby is far more plausible for a new preacher to obtain than is fame across the whole of a huge province the size of half of Mesopotamia. At the time, in Judaism, disease was seen as an atonement for sin, and so healing was seen as forgiveness of sin, and was usually attributed to charismatic and devout priests and other religious leaders.

Matthew states that people came from several other regions to see Jesus, implying that the Syrians/Synorians had spread his fame even further. Specifically, Matthew lists Decapolis, Jerusalem, Judea, and Peraea (identified as beyond the Jordan River). Decapolis isn't a single location but ten, it literally means the ten towns, and refers to Greek settlements in Palestine, while Galilee (where Jesus is), Judea, and Peraea, constitute the remainder of the traditional Jewish region, and Syria constitutes the remainder of the lands that traditionally were seen as having once been under David and Solomon's control. Thus, people from the entire Holy Land are described by Matthew as amassing to experience Jesus. However, it is important to point out that the capitals of the previous Kingdom of Israel and Kingdom of Judah were seen as quasi-independent, thus the mention of Jerusalem, the prior capital of Judah/Judea, in its own right, but this leaves Samaria, the prior capital of Israel, without mention. This is generally seen by scholars as part of a continued slur against the Samaritans that Matthew perpetuates throughout, since they were a group that held themselves to be the original form of Judaism, but the Jews viewed them as heretics.

[edit] Teachings

As well as more general sermons, such as the Sermons on the Mount and on the Plain, which touch briefly on several different topics, the Biblical narrative portrays Jesus as also having concentrated on particular themes and topics. The biblical narrative of the Synoptic Gospels mentions and details several instances in which these subjects are more specifically discussed; the Gospel of John appears less interested in the teachings, concentrating instead more on Jesus' life and attributing various miracles to him.

[edit] General ethics

When asked what is the greatest commandment, Jesus is portrayed by the Gospels of Mark[12:28–34] and of Matthew[22:34-40] as stating that the first two commandments, and the greatest, are

- One should love God with one's entire heart, soul, mind, and strength

- One should love one's neighbour as one would love oneself

Though it isn't clear what commandment refers to, the latter part of the first of these two is a quotation from the Ritual Decalogue in Deuteronomy. The second, however, does not appear as one of either set of Ten Commandments, instead appearing in the Holiness Code,[Lev. 19:18] and therefore it is likely that commandment is a reference to the 613 mitzvot of Jewish law. The first part of the first commandment given by Jesus is from the Shema, the most important prayer in Judaism, suggesting to several scholars that when the earliest of the Synoptic Gospels was written the Christian groups still retained Jewish prayer formats.[5] [6] The second commandment, the Great Commandment, essentially a formulation of the Golden Rule, is also present in the Pauline Epistles,[7] where it is portrayed as the summary of Jewish law (i.e., as the most important command, not the second most important), and textual critics argue that this is likely where Mark ultimately derived the passage from.[8]

The Gospel of Mark, but not that of Matthew, states that the man who posed the question responds that these commands are wise teachings, and so Jesus replies that the man is "not far from the kingdom of God". While being not far from God can be seen in the sense of close to knowledge of God, and this is the usual interpretation, more literal minded Christians have argued that far here refers to a spatial distance from God, i.e., that Jesus is categorically stating that he is God (Kilgallen 237).

The Gospel of John also has one commandment, often called The New Commandment: "A new commandment I give unto you, that you love one another."[John 13:31-35]

[edit] Establishmentarianism

In both Mark 12:13-17 and the gnostic Gospel of Thomas,[9] when presented with a coin and questioned about taxation, Jesus is stated to have said that one should give to Caesar what is Caesar's and to God what is God's. This passage has often been used in arguments on the nature of the relationship between church and state in North America and in questions of disestablishmentarianism and antidisestablishmentarianism in the UK, and similar questions in other western countries.

In Mark's gospel, this saying is framed as the response of Jesus to a clever trap laid by the Sadducees, who had sent the Pharisees together with supporters of Herod Antipas to him; the supporters of Herod[10] favoured Rome and hence the payment of taxes to it, while the Pharisees (in particular the Zealot faction) opposed such taxes and regarded them as a form of oppression, hence favouring one option above the other would have insulted the other side. In the gnostic gospel of Thomas there is no such framing, as is the case with most sayings in Thomas, and its presence in Thomas as well as Mark makes it plausible that the saying originated in the Q document, which also is a collection of sayings without any narrative context.

Mark also specifies that the coin in question is a denarius, and was hence marked with the image of the Caesar, signifying ownership. The coin thus is technically Rome's anyway, and so giving it back by paying it as tax could be logically argued as changing nothing. On the other hand, the instruction to give to God could be argued to imply that one ought to fulfil religious obligations as strongly as secular ones. In Thomas, the saying has the additional instruction to give [Jesus] what is [his], raising Christological questions since Jesus is presented as a distinct third division apart from God and from Secular Authority, as well as more obvious questions of what exactly is meant by it. Further interpretations of this passage alude to the statement in Genesis 1:26-27 that man and woman were created "in the image of God." Therefore, the coin, which bore Caesar's image, was rightly to be rendered to Caesar, and people, which bore God's image, were rightly to render their obedience to God.

[edit] Ritual cleanliness

The Gospel of Mark and the apocryphal Gospel of Thomas present Jesus as making a significant statement downplaying the Pharisaical laws about ritual cleanliness:

- Nothing outside a man can make him ritually unclean by going into him. Rather, it is what comes out of a man that makes him ritually unclean.[Mark 7:15]

Unlike Thomas,[11] Mark's biblical gospel adds an explanation, stating that it is the evils of sexual immorality, theft, murder, adultery, greed, malice, deceit, lewdness, envy, slander, arrogance, and folly, which make someone ritually unclean, not what they eat. The Gospel of Thomas has a simpler implication, since rather than stating that it is what comes out of a man that makes him unclean, Thomas states that it is what comes out of a man's mouth, i.e., his words are what condemn him. Since the Thomas version of the saying about ritual cleanliness directly contrasts that which goes into the mouth with that which comes out of it, rather than the weaker contrast between what one eats and what one produces, many scholars think it is the Thomas version of the saying that is more original than that present in Mark.

As is common in sayings like this, the point of the latter part of the passage is frequently ignored and much more literature is devoted to considering the implications of the former section. The passage has been considered by most Christians over the centuries to imply that Christians are not bound by the laws of unclean food that apply in Judaism. Kilgallen (135) argues that which food one eats matters not to God. The passage also played a central role in the arguments in the early church between Pauline Christianity and Jewish Christianity, as to how much of Old Testament law one ought obey.[12]

In Mark 7:1-8, the saying is framed as a response by Jesus to the Pharisees who were criticising how some of the followers of Jesus did not follow the ritual Jewish practice of washing their hands before eating. Mark also has Jesus refer to a quote from the Book of Isaiah about superficial adherence to the law,[Isa. 29:13] and instead following rules laid by men. Mark more specifically portrays Jesus as condemning the Pharisees as hypocrites for letting people give money to the priests (theoretically an offering to God, see korbanas) in order to be excused from helping their own parents, violating one of the commands of the Ritual Decalogue. Similar, but more general, criticism also appears in the introduction to the saying in Thomas, where Jesus is presented as sarcastically complaining that it is sinful to fast, prayer leads to condemnation, and charity harms one's spirit. Mark's claim about the Pharisees allowing people to buy their way out of the Ritual Decalogue is not, however, found in other sources of the period, although there are hints of the possibility in some rabbinic texts (Miller 29), and it may simply be the case that Mark has refined the more general introduction present also in Thomas into a more specific case.

The Jewish Encyclopedia article on Gentile: Gentiles May Not Be Taught the Torah notes the following reconciliation:

| “ | R. Emden, in a remarkable apology for Christianity contained in his appendix to "Seder 'Olam" (pp. 32b-34b, Hamburg, 1752), gives it as his opinion that the original intention of Jesus, and especially of Paul, was to convert only the Gentiles to the seven moral laws of Noah and to let the Jews follow the Mosaic law — which explains the apparent contradictions in the New Testament regarding the laws of Moses and the Sabbath. | ” |

[edit] Innocence

The Synoptic Gospels portray Jesus as asserting very strongly that innocence ought to be preserved, arguing that it is better for someone to be cast into the sea with a millstone around one's neck, than to destroy the innocence of children.[Mk. 9:42] Furthermore, it is asserted that one should dispose of other things which bring sin, even to the extreme of cutting off one's own hands and plucking out one's eyes, if their action results in sinfulness, arguing that it is better to be maimed in heaven than to be fully functional in hell.[Mk. 9:43-49] [13]

The Synoptics describe Jesus as insisting that whoever welcomes children in his name also welcomes him.[Mk. 10:13-16] When the disciples question which of them would be the greatest, Jesus rebukes them saying that he who wishes to be first must be last, and the least shall be the greatest, emphasising that unless they receive the kingdom of God like a child they will never enter.[Mk. 9:33-37] While some argue that the children are metaphorical in this saying, being a reference to childlike dependence and unquestioning acceptance of God (Brown et al. 618), the ancient gnostics argued that it referred instead to reclaiming innocence and curiosity about the world.

[edit] Divorce

In Jewish law, men were permitted to divorce their wives simply by writing out a formal certificate of divorce, but Jesus is portrayed by the Gospels of Mark[Mark 10:1–12] and of Matthew as arguing that divorce is invalid, essentially arguing that any marriage subsequent to a divorce, whether by the man or by the woman, constitutes adultery. In Mark, Jesus is described as attempting to justify his stance by combining two parts of Genesis,[Gen. 1:27] [2:24] referring to the creation of the sexes, and how the two become one flesh by marriage. According to the Documentary Hypothesis, however, these two passages originally came from quite separate sources. In Matthew, but not in Mark, there is an explicit exception to this prohibition, namely that divorce is permitted if adultery has been committed by one or more of the spouses.

Historically, the teaching was upheld by official Christian doctrine, and there remains a general prohibition of divorce in the Roman Catholic Church, and the Eastern Orthodox Church, although the exception is retained in the case of adultery and the Pauline privilege. In the time of Jesus, the view of divorce as an evil was shared primarily with the Essenes, a group with which Jesus is often considered by scholars to have had significant connections (Brown 141). Amongst gnostic groups, who generally had what would now be considered liberal stances, divorce was also frequently rejected, since it was argued to be a thing whose purpose could only be related to carnal desires, and hence logically inappropriate for people who are trying to escape the carnal world. Many gnostics also argued that the Bible supported their interpretation since there is also, in Matthew's gospel and in the biblical writing of the apostle Paul, an emphasis on celibacy being the best choice, which also was a rejection of carnal desire.

[edit] Poverty

During his Journey to Jerusalem, Jesus is described by the Gospel of Mark as meeting a rich man, who addresses him as Good Teacher. However, Mark 10:17–31 states that Jesus responds by saying none is good but God alone, seemingly rejecting the form of address, but in a way which also appears to exclude Jesus from being God, and hence forming one of the main issues in Christology.[14] The rich man is described as explaining that he has always kept the commandments, presumably the ten commandments or the Didache or the 613 mitzvot, Jesus stating that he is aware that the man knows them.

The narrative goes on to portray Jesus as arguing that the man should give up everything, giving it to the poor, and only then follow Jesus, since it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God.

Though quite radical to the Pharisees and Sadduccees, non-ownership was the normal way of life for Essenes, who lived at varying levels of asceticism, and this is one of the reasons that many scholars suspect that Jesus was originally part of an Essene group. The insistence on giving up ownership of riches was one of the major arguments between different monastic orders in the mediaeval world, with the Franciscans in particular arguing that Jesus' teaching meant the church should not seek riches, but the Pope, at that time living in great luxury, ruled otherwise, and the non-ownership restrictions on mendicant orders were lifted. Despite their separation from the papacy, conservative protestants have traditionally supported this papal line.

[edit] Resurrection of the dead

Jesus preached the resurrection. His parable of Lazarus and Dives portrays the common Jewish belief of the time that the righteous and unrighteous await Judgment Day in peace (in the bosom of Abraham) or in torment, respectively (see particular judgment).

The belief in the resurrection of the dead was largely a late innovation in ancient Jewish thought, and the Sadducees, who only considered the Pentateuch to be divinely inspired, considered it to be a false teaching. Since Deuteronomy decrees the obligation of levirate marriage,[Deut. 25:5] i.e., the brother of a dead man must marry the dead man's wife if the wife is childless, the logical conclusion is that if there are seven brothers, each dying for some reason, the wife could potentially have been married seven times, and hence if the dead were resurrected she would find herself in a highly polygamous situation. According to the Gospel of Mark,[Mark 12:18-27] the Sadducees used this logical conundrum to challenge the idea of the resurrection of the dead, but Jesus argues that the resolution is simple—there will be no marriage after the resurrection and the people will be like the angels in heaven.

Jesus is described by Mark as going on to justify the doctrine of resurrection, by referring to the story of the burning bush, in which God is described as stating, at one moment in time, that he is the God of each of the three Patriarchs—Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, using the present tense—I am ... not I was. Mark portrays Jesus as stating that, since God is God of the Living and not of the dead, Abraham, Isaac and Jacob are still living, i.e., resurrection.

Inga kommentarer:

Skicka en kommentar