Christendom

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Christendom,[1] or the Christian world,[2] has several meanings. In a cultural sense it refers to the worldwide community of Christians, adherents of Christianity. This community numbers in the billions of people[3] of the world population, and is spread across many different nations and ethnic groups connected only by faith in Christ and observance of the Bible.[4] In a historical or geopolitical sense the term usually refers collectively to Christian majority countries or countries in which Christianity dominates[1] or was a territorial phenomenon.

Contents[hide] |

[edit] Terminology and usage

The term Christendom is developed from the Latin word Christianus. The Christian world is also known collectively as the Church of Christ or Corpus Christianum. The Latin term Corpus Christianum is often translated as the Christian body, meaning the community of all Christians. The Christian polity, embodying a less secular meaning, can be compatible with the idea of both a religious and a temporal body: Corpus Christianum. The Corpus Christianum can be seen as a Christian equivalent of the Muslim Ummah. The Kingdom of God is also frequently used, denoting that the Christian world is within (or among) people.[5]

"Christendom" is used in this article to denote the global community of Biblical Christianity. Christendom as such is set on the appellation of religious aspects. However, the word is also used with its other meaning to frame true Christianity. A more secular meaning can denote that the term Christendom refers to Christians considered as a group, the "Political Christian World", as an informal cultural hegemony that Christianity has traditionally enjoyed in the West.

[edit] History

[edit] Early Christendom

In the beginning of Christendom, early Christianity was a religion spread in the Greek/Roman world and beyond as a 1st century Jewish sect[6], which historians refer to as Jewish Christianity. It may be divided into two distinct phases: the apostolic period, when the first apostles were alive and organising the Church, and the post-apostolic period, when an early episcopal structure developed, whereby bishoprics were governed by bishops (overseers).

The post-apostolic period concerns the time roughly after the death of the apostles when bishops emerged as overseers of urban Christian populations. The earliest recorded use of the terms Christianity (Greek Χριστιανισμός) and Catholic (Greek καθολικός), dates to this period, the 2nd century, attributed to Ignatius of Antioch c. 107.[7] Early Christendom would close at the end of imperial persecution of Christians after the ascension of Constantine the Great and the Edict of Milan in AD 313 and the First Council of Nicaea in 325.

[edit] Middle Christendom

"Christendom" has referred to the medieval and renaissance notion of the Christian world as a sociopolitical polity. In essence, the earliest vision of Christendom was a vision of a Christian theocracy, a government founded upon and upholding Christian values, whose institutions are spread through and over with Christian doctrine. In this period, members of the Christian clergy wield political authority. The specific relationship between the political leaders and the clergy varied but, in theory, the national and political divisions were at times subsumed under the leadership of the church as an institution. This would tempt Church leaders and political leaders alike throughout the time in European history.

Emperor Constantine issued the Edict of Milan in 313 proclaiming toleration for the Christian religion, and convoked the First Council of Nicaea in 325 whose Nicene Creed included belief in "one holy catholic and apostolic Church". Christianity became the state religion of the Empire in 392 when Theodosius I prohibited the practice of pagan religions. The Church gradually became a defining institution of the Empire.

As the Western Roman Empire disintegrated into feudal kingdoms and principalities, the concept of Christendom changed as the western church became independent of the Emperor and the Christians of the Eastern Roman Empire. The Byzantine Empire came to see themselves as the last bastion of Christendom. Christendom would take a turn with the rise of the Franks, a Germanic tribe who converted to the Christian faith and entered into communion with Rome. On Christmas Day 800 AD, Pope Leo III made the fateful decision to switch his allegiance from the emperors in Constantinople and crowned Charlemagne, the king of the Franks, as the Emperor of what came to be known as the Holy Roman Empire. This empire created a alternative definition of Christendom in contrast to the Byzantine Empire. The question of what constituted true Christendom would occupy political and religious leaders up into the modern era.

After the collapse of Charlemagne's empire, the southern remnants of the Holy Roman Empire became a collection of states loosely connected to the Holy See of Rome. Tensions between Pope Innocent III and secular rulers ran high, as the pontiff exerted control over their temporal counterparts in the west and vice versa. The pontificate of Innocent III is considered the height of temporal power of the papacy. The Corpus Christianum described the then current notion of the community of all Christians united under the Roman Catholic Church. This community was to be guided by Christian values in its politics, economics and social life. Its legal basis was the corpus iuris canonica (body of canon law).

In the East, Christendom became more defined as the Byzantine Empire's gradual loss of territory to an expanding Islam and the muslim conquest of Persia. This caused Christianity to become important to the Byzantine identity. After the East-West Schism which divided the Church religiously, there had been the notion of a universal Christendom that included the East and the West. The Byzantines divided themselves in the Byzantine rite of the Eastern Orthodox Church and the eastern rite of the Catholic Church. The political reunion with the west, after the East-West schism, was put asunder by the Fourth Crusade when Crusaders conquered the Byzantine capital of Constantinople and hastened the decline of the Byzantine Empire on the path to its destruction.[8] With the breakup of the Byzantine Empire into individual nations with nationalist Orthodox Churches, the term Christendom described Western Europe, Catholicism, Orthodox Byzantines, and other Eastern rites of the Church.

[edit] Late Christendom

The Western Church's peak of authority over all European Christians and their common endeavors of the Christian community — for example, the Crusades, the fight against the Moors in the Iberian Peninsula and that against the Ottomans in the Balkans — helped to develop a sense of communal identity against the obstacle of Europe's deep political divisions. But this authority also fostered the Inquisition and anti-Jewish pogroms, to root out divergent elements and create a religiously uniform community.

Christendom ultimately was led into specific crisis in the late Middle Ages, when the kings of France managed to establish a French national church during the 14th century and the papacy became ever more aligned with the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation. Known as the Western Schism, western Christendom was a split between three men, who were driven by politics rather than any real theological disagreement for simultaneously claiming to be the true pope. The Avignon Papacy developed a reputation of corruption that estranged major parts of Western Christendom. The schism was ended by the Council of Constance.

Before the modern period, Christendom was in a general crisis in the time of the Renaissance Popes because of the moral laxity of these pontiffs and their willingness to seek and rely on temporal power as secular rulers did. The Renaissance Church became a secular institution in this period, shedding its spiritual roots, with insatiable greed for material wealth and temporal power. The Italian Renaissance produced little of what could be considered great ideas or institutions by which men living in society could be held together in harmony.[citation needed]. The Roman Church fell into neglect under the Renaissance popes, whose fall from spiritual grace sparked Reformations.

The Reformation and the ensuing rise of independent states caused the term "Christendom" to take on a more general meaning in Western Europe signifying countries which were predominantly Christian as opposed to Islamic or pagan countries. Catholics at the time advocated Christendom's restoration and argued that, with the division of Protestantism into many denominations, Christendom could only apply to the civilization of Catholic nations that espoused the doctrine of the Social Reign of Christ the King. The Catholic nations did represent a large portion of European Christians and the Corpus Christianum initially was composed of the Christian community of these nations, rather than all Christians worldwide. But developments in western philosophy and European events were critical in the change of the notion of the Corpus Christianum.[9] The Hundred Years' War accelerated the process of transforming France from a feudal monarchy to a centralized state. The rise of strong, centralized monarchies[10] denoted the European transition from feudalism to capitalism. By the end of the Hundred Years' War, both France and England were able to raise enough money through taxation to create independent standing armies. In the Wars of the Roses, Henry Tudor took the crown of England. His heir, the absolute king Henry VIII establishing the English church.

[edit] Classical culture

[edit] Art and literature

[edit] Writings and poetry

Christian literature is writing that deals with Christian themes and incorporates the Christian world view. This constitutes a huge body of extremely varied writing. Christian poetry is any poetry that contains Christian teachings, themes, or references. The influence of Christianity on poetry has been great in any area that Christianity has taken hold. Christian poems often directly reference the Bible, while others provide allegory.

[edit] Supplemental arts

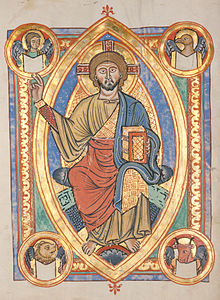

Christian art is art produced in an attempt to illustrate, supplement and portray in tangible form the principles of Christianity. Virtually all Christian groupings use or have used art to some extent. The prominence of art and the media, style, and representations change; however, the unifying theme is ultimately the representation of the life and times of Jesus and in some cases the Old Testament. Depictions of saints are also common, especially in Anglicanism, Roman Catholicism, and Eastern Orthodoxy.

[edit] Illumination

An illuminated manuscript is a manuscript in which the text is supplemented by the addition of decoration. The earliest surviving substantive illuminated manuscripts are from the period AD 400 to 600, primarily produced in Ireland, Constantinople and Italy. The majority of surviving manuscripts are from the Middle Ages, although many illuminated manuscripts survive from the 15th century Renaissance, along with a very limited number from Late Antiquity.

Most illuminated manuscripts were created as codices, which had superseded scrolls; some isolated single sheets survive. A very few illuminated manuscript fragments survive on papyrus. Most medieval manuscripts, illuminated or not, were written on parchment (most commonly of calf, sheep, or goat skin), but most manuscripts important enough to illuminate were written on the best quality of parchment, called vellum, traditionally made of unsplit calfskin, though high quality parchment from other skins was also called parchment.

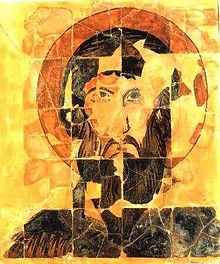

[edit] Iconography

Christian art began, about two centuries after Christ, by borrowing motifs from Roman Imperial imagery, classical Greek and Roman religion and popular art. Religious images are used to some extent by the Abrahamic Christian faith, and often contain highly complex iconography, which reflects centuries of accumulated tradition. In the Late Antique period iconography began to be standardised, and to relate more closely to Biblical texts, although many gaps in the canonical Gospel narratives were plugged with matter from the apocryphal gospels. Eventually the Church would succeed in weeding most of these out, but some remain, like the ox and ass in the Nativity of Christ.

An icon is a religious work of art, most commonly a painting, from Eastern Orthodox Christianity. Christianity has used symbolism from its very beginnings.[11] In both East and West, numerous iconic types of Christ, Mary and saints and other subjects were developed; the number of named types of icons of Mary, with or without the infant Christ, was especially large in the East, whereas Christ Pantocrator was much the commonest image of Christ.

Christian symbolism invests objects or actions with an inner meaning expressing Christian ideas. Christianity has borrowed from the common stock of significant symbols known to most periods and to all regions of the world. Religious symbolism is effective when it appeals to both the intellect and the emotions. Especially important depictions of Mary include the Hodegetria and Panagia types. Traditional models evolved for narrative paintings, including large cycles covering the events of the Life of Christ, the Life of the Virgin, parts of the Old Testament, and, increasingly, the lives of popular saints. Especially in the West, a system of attributes developed for identifying individual figures of saints by a standard appearance and symbolic objects held by them; in the East they were more likely to identified by text labels.

Each saint has a story and a reason why he or she led an exemplary life. Symbols have been used to tell these stories throughout the history of the Church. A number of Christian saints are traditionally represented by a symbol or iconic motif associated with their life, termed an attribute or emblem, in order to identify them. The study of these forms part of iconography in Art history. They were particularly

[edit] Architecture

Christian architecture encompasses a wide range of both secular and religious styles from the foundation of Christianity to the present day, influencing the design and construction of buildings and structures in Christian culture.

Buildings were at first adapted from those originally intended for other purposes but, with the rise of distinctively ecclesiastical architecture, church buildings came to influence secular ones which have often imitated religious architecture. In the 20th century, the use of new materials, such as concrete, as well as simpler styles has had its effect upon the design of churches and arguably the flow of influence has been reversed. From the birth of Christianity to the present, the most significant period of transformation for Christian architecture in the west was the Gothic cathedral. In the east, Byzantine architecture was a continuation of Roman architecture.

[edit] Philosophy

Christian philosophy is a term to describe the fusion of various fields of philosophy with the theological doctrines of Christianity. Scholasticism, which means "that [which] belongs to the school", and was a method of learning taught by the academics (or school people) of medieval universities circa 1100–1500. Scholasticism originally started to reconcile the philosophy of the ancient classical philosophers with medieval Christian theology. Scholasticism is not a philosophy or theology in itself but a tool and method for learning which places emphasis on dialectical reasoning.

[edit] Christian civilization

[edit] Medieval conditions

The Byzantine Empire, which was the most sophisticated culture during antiquity, suffered under muslim conquests limiting its scientific prowess during the Medieval period. Christian Western Europe had suffered a catastrophic loss of knowledge following the fall of the Western Roman Empire. But thanks to the Church scholars such as Aquinas and Buridan, the West carried on at least the spirit of scientific inquiry which would later lead to Europe's taking the lead in science during the Scientific Revolution using translations of medieval works.

Medieval technology refers to the technology used in medieval Europe under Christian rule. After the Renaissance of the 12th century, medieval Europe saw a radical change in the rate of new inventions, innovations in the ways of managing traditional means of production, and economic growth.[12] The period saw major technological advances, including the adoption of gunpowder and the astrolabe, the invention of spectacles, and greatly improved water mills, building techniques, agriculture in general, clocks, and ships. The latter advances made possible the dawn of the Age of Exploration. The development of water mills was impressive, and extended from agriculture to sawmills both for timber and stone, probably derived from Roman technology. By the time of the Domesday Book, most large villages in Britain had mills. They also were widely used in mining, as described by Georg Agricola in De Re Metallica for raising ore from shafts, crushing ore, and even powering bellows.

Significant in this respect were advances within the fields of navigation. The compass and astrolabe along with advances in shipbuilding, enabled the navigation of the World Oceans and thus domination of the worlds economic trade. Gutenberg’s printing press made possible a dissemination of knowledge to a wider population, that would not only lead to a gradually more egalitarian society, but one more able to dominate other cultures, drawing from a vast reserve of knowledge and experience.

[edit] Renaissance innovations

During the Renaissance, great advances occurred in geography, astronomy, chemistry, physics, math, manufacturing, and engineering. The rediscovery of ancient scientific texts was accelerated after the Fall of Constantinople, and the invention of printing which would democratize learning and allow a faster propagation of new ideas. Renaissance technology is the set of artifacts and customs, spanning roughly the 14th through the 16th century. The era is marked by such profound technical advancements like the printing press, linear perspectivity, patent law, double shell domes or Bastion fortresses. Draw-books of the Renaissance artist-engineers such as Taccola and Leonardo da Vinci give a deep insight into the mechanical technology then known and applied.

Renaissance science spawned the Scientific Revolution; science and technology began a cycle of mutual advancement. The Scientific Renaissance was the early phase of the Scientific Revolution. In the two-phase model of early modern science: a Scientific Renaissance of the 15th and 16th centuries, focused on the restoration of the natural knowledge of the ancients; and a Scientific Revolution of the 17th century, when scientists shifted from recovery to innovation.

[edit] Biblical science

The various books of the Old Testament and the New Testament contain descriptions of the physical world, and can be considered a source of information of the history of science in the Iron Age Levant. Proponents of "Biblical knowledge" over this prefer readings that would explain discoveries made historically. Items that are cited, among others, include agriculture, astronomy and life origins, biology, ecology, electricity, mathematics, medical knowledge (such as mental health and sanitation).

For all the scientific investigations regarding sacred literature, there has been a cause far more general and powerful, for it is a cause surrounding and permeating all.[13][14] If, in the atmosphere generated by the earlier developed sciences, the older growths of biblical interpretation have drooped and withered and are evidently perishing, new and better growths have arisen with roots running down into the sciences.[14][15] While researches in these sciences have established the fact that accounts formerly to be special revelations, they have also begun to impress upon the intellect and conscience of the thinking world the fact that the religious and moral truths thus disengaged from the old masses of myth and legend are all the more venerable and authoritative, and that all individual or national life of any value must be vitalized by them.[14]

If, then, modern science in general has acted powerfully to dissolve away older theological interpretation, it has also been active in a reconstruction and recrystallization of truth.[14] In the light thus obtained the sacred text has been transformed: out of the old chaos has come order; out of the old confused mass of hopelessly conflicting statements in religion and morals has come, in obedience to this new conception of development, the idea of a sacred literature which mirrors the most striking evolution of morals and religion in the history of the human race.[14] Thus it is that, with the keys furnished by this new race of biblical scholars, the way has been opened to treasures of thought which have been inaccessible to theologians for two thousand years.[14] Proponents of "Biblical foreknowledge" beyond this prefer readings that would anticipate discoveries historically made only in modern times.

[edit] Biblical Creationism

Christian fundamentalists adhere to a belief known as Bible scientific foresight advocating that certain Bible passages show an understanding of science beyond that presumed to exist at the time the it was written. Creationism is a specific Christian belief that humanity, life, the Earth, and the universe were created in their original form by a deity. In this belief systems, this is the Abrahamic God.

[edit] Modern Christendom

In modern history, the Reformation and rise of modernity in the early 16th century entailed a change in the Corpus Christianum. The Peace of Augsburg in 1555 officially ended the idea that all Christians could be united under one church. The principle of cuius regio, eius religio ("whose the region is, his religion") established the religious, political and geographic divisions of Christianity, and this was established in international law with the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648, which legally ended the concept of a single Christian hegemony, i.e. the "One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Church" of the Nicene Creed. Each government determined the religion of their own state. Christians living in states where their denomination was not the established church were guaranteed the right to practice their faith in public during allotted hours and in private at their will. With the Treaty of Westphalia, the Wars of Religion came to an end, and in the Treaty of Utrecht of 1713 the concept of the sovereign national state was born. The Corpus Christianum has since existed with the modern idea of a tolerant and diverse society consisting of many different communities.

[edit] Geographic spread

Christianity is the predominant religion in Europe, Russia, the Americas, the Philippines, Southern Africa, Central Africa and East Africa.[16] There are also large Christian communities in other parts of the world, such as Central Asia, where Christianity is the second-largest religion after Islam. The United States is the largest Christian country in the world by population, followed by Brazil and Mexico[17].

Many Christian not only live in, but also have an official status in a state religion of the following nations: Argentina (Roman Catholic Church)[18][19], Armenia (Armenian Apostolic Church)[20], Bolivia (Roman Catholic Church)[21], Costa Rica (Roman Catholic Church)[22], Denmark (Danish National Church)[23], El Salvador (Roman Catholic Church)[24], England (Church of England)[25], Greece (Church of Greece), Iceland (Church of Iceland)[26], Liechtenstein (Roman Catholic Church)[27], Malta (Roman Catholic Church)[28], Monaco (Roman Catholic Church)[29], Romania (Romanian Orthodox Church), Norway (Church of Norway)[30], Vatican City (Roman Catholic Church)[31], Switzerland (Roman Catholic Church, Swiss Reformed Church and Christian Catholic Church of Switzerland) and Georgia (Georgian Orthodox Church).

[edit] Demographics

The estimated number of Christians in the world ranges from 1.5 billion[3] to 2.3 billion people[3]. Composed of around 34,000 different denominations, Christianity is the world's largest religion.[32] Christians have composed about 33 percent of the world's population for around 100 years.

[edit] Notable Christian organizations

A religious order is a lineage of communities and organizations of people who live in some way set apart from society in accordance with their specific religious devotion, usually characterized by the principles of its founder's religious practice. In contrast, the term Holy Orders is used by many Christian churches to refer to ordination or to a group of individuals who are set apart for a special role or ministry. Historically, the word "order" designated an established civil body or corporation with a hierarchy, and ordinatio meant legal incorporation into an ordo. The word "holy" refers to the Church. In context, therefore, a holy order is set apart for ministry in the Church. Religious orders are composed of initiates (laity) and, in some traditions, ordained clergies.

Various organizations include:

- Roman Catholic religious orders are the major form of consecrated life in the Roman Catholic Church. They are organisations of laity and/or clergy who live a common life following a religious rule under the leadership of a religious superior. (ed., see Category:Roman Catholic orders and societies for a particular listing.)

- Anglican religious orders are communities of laity and/or clergy in the Anglican Communion who live under a common rule of life. (ed., see Category:Anglican organizations for a particular listing)

[edit] Christianity law and ethics

[edit] Church and state framing

Within the framework of Christianity, there are at least three possible definitions for Church law. One is the Torah/Mosaic Law (from what Christians consider to be the Old Testament) also called Divine Law or Biblical law. Another is the instructions of Jesus of Nazareth in the Gospel (sometimes referred to as the Law of Christ or the New Commandment or the New Covenant). A third is canon law which is the internal ecclesiastical law governing the Roman Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox churches, and the Anglican Communion of churches.[33] The way that such church law is legislated, interpreted and at times adjudicated varies widely among these three bodies of churches. In all three traditions, a canon was initially a rule adopted by a council (From Greek kanon / κανών, Hebrew kaneh / קנה, for rule, standard, or measure); these canons formed the foundation of canon law.

Christian ethics in general has tended to stress the need for grace, mercy, and forgiveness because of human weakness and developed while Early Christians were subjects of the Roman Empire. From the time Nero blamed Christians for setting Rome ablaze (64 AD) until Galarius (311 AD), persecutions against Christians erupted periodically. Consequently, Early Christian ethics included discussions of how believers should relate to Roman authority and to the empire.

Under the Emperor Constantine I (312-337), Christianity became a legal religion. While some scholars debate whether Constantine's conversion to Christianity was authentic or simply matter of political expediency, Constantine's decree made the empire safe for Christian practice and belief. Consequently, issues of Christian doctrine, ethics and church practice were debated openly, see for example the First Council of Nicaea and the First seven Ecumenical Councils. By the time of Theodosius I (379-395), Christianity had become the state religion of the empire. With Christianity in power, ethical concerns broaden and included discussions of the proper role of the state.

Render unto Caesar… is the beginning of a phrase attributed to Jesus in the synoptic gospels which reads in full, "Render unto Caesar the things which are Caesar’s, and unto God the things that are God’s". This phrase has become a widely quoted summary of the relationship between Christianity and secular authority. The gospels say that when Jesus gave his response, his interrogators "marvelled, and left him, and went their way." Time has not resolved an ambiguity in this phrase, and people continue to interpret this passage to support various positions that are poles apart. The traditional division, carefully determined, in Christian thought is the state and church have separate spheres of influence.

Thomas Aquinas thoroughly discussed that human law is positive law which means that it is natural law applied by governments to societies. All human laws were to be judged by their conformity to the natural law. An unjust law was in a sense no law at all. At this point, the natural law was not only used to pass judgment on the moral worth of various laws, but also to determine what the law said in the first place. This could result in some tension.[34] Hardly a single portion of ethics does Aquinas present to us but is enriched with his keen philosophical commentaries. Late ecclesiastical writers followed in his footsteps.

[edit] Religious republics

A Christian Republic is most broadly defined as a republic with a state religion of Christianity. Although in general the term means a republic of a Christian orientation. That orientation usually means that the state religion effects the laws and the political parties are Christian oriented.

[edit] Democratic ideology

Christian democracy is a political ideology that seeks to apply Christian principles to public policy. It emerged in nineteenth-century Europe, largely under the influence of Catholic social teaching. In a number of countries, the democracy's Christian ethos has been diluted by secularisation. In practice, Christian democracy is often considered conservative on cultural, social and moral issues and progressive on fiscal and economic issues. In places, where their opponents have traditionally been secularist socialists and social democrats, Christian democratic parties are moderately conservative, whereas in other cultural and political environments they can lean to the left.

[edit] Women roles

Attitudes and beliefs about the roles and responsibilities of women in Christianity vary considerably today as they have throughout the last two millennia — evolving along with or counter to the societies in which Christians have lived. The Bible and Christianity historically have been interpreted as excluding women from church leadership and placing them in submissive roles in marriage. Male leadership has been assumed in the church and within marriage, society and government.[35]

Some contemporary writers describe the role of women in the life of the church as having been downplayed, overlooked, or denied throughout much of Christian history. Paradigm shifts in gender roles in society and also many churches has inspired reevaluation by many Christians of some long-held attitudes to the contrary. Christian egalitarians have increasingly argued for equal roles for men and women in marriage, as well as for the ordination of women to the clergy. Contemporary conservatives meanwhile have reasserted what has been termed a "complementarian" position, promoting the traditional belief that the Bible ordains different roles and responsibilities for women and men in the Church and family.

[edit] Major Christian denominations

A schematic of Christian denominational taxonomy. The different width of the lines (thickest for "Protestantism" and thinnest for "Oriental Orthodox" and "Nestorians") is without objective significance. Protestantism in general, and not just Restorationism, claims a direct connection with Early Christianity. |

A Christian denomination is an identifiable religious body under a common name, structure, and doctrine within Christianity. Worldwide, Christians are divided, often along ethnic and linguistic lines, into separate churches and traditions. Various denominations, such as the Jehovah's Witnesses, make particular distinctions in their literature.[36] Technically, divisions between one group and another are defined by church doctrine and church authority. Centering around language of professed Christianity and true Christianity, issues that separate one group of followers of Jesus from another include:

- Apostolic succession,

- Biblical authority,

- Biblical criticism,

- Biblical inerrancy,

- Biblical infallibility,

- Biblical inspiration,

- Biblical interpretation,

- Papal primacy, and

- Views of Jesus (Christology).

Christianity is composed of, but not limited to, five major branches of Churches: Catholicism, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Anglican and Protestant; some groupings include Anglicans amongst Protestants. The Assyrian Church of the East is also a distinct Christian body, but is much smaller in adherents and geographic scope. Each of these five branches has important subdivisions. Because the Protestant subdivisions do not maintain a common theology or earthly leadership, they are far more distinct than the subdivisions of the other four groupings. Denomination typically refers to one of the many Christian groupings including each of the multitude of Protestant subdivisions.

[edit] Sizes of denomination

Catholicism is the largest denomination, comprising just over half of Christians worldwide.

In Christendom, the largest denominations are:

- The Catholic Church - 1.2 billion

- Protestantism - 540 million

- Eastern Orthodoxy - 210 million

- Anglicanism - 77 million

- Oriental Orthodoxy - 75 million

- Nontrinitarianism - 26 million

- Nestorianism - 1 million

[edit] Christendom and other beliefs

In the interaction between Christendom and other belief systems,[37] men and women when not at war with their neighbors have always made an effort to understand the Other (not least because understanding is a strategy for defense, but also because for as long as there is dialogue wars are delayed). Such interactions have led to various interfaith dialogue events. History records many examples of interfaith initiatives and dialogue throughout the ages. In the field of comparative religion, the interactions connects fundamental ideas in Christianity with similar ones in other religions. Christianity and other religions appear to share some elements. Regarding Christianity's relationship with other world beliefs, Christianity and other beliefs have differences and similarities in connection with each other.

[edit] Judaic world

Although Christianity and Judaism share historical roots, these two religions diverge in fundamental ways. Judaism places emphasis on actions, focusing primary questions on how to respond to the covenant God made with Israelites and Proselytes, as recorded in the Torah. Though Judeo-Christian tradition emphasizes continuities and convergences between the two religions, there are many other areas in which the faiths diverge.

[edit] Muslim world

Christianity and Islam share their origins in the Abrahamic tradition, as well as Judaism. Islam accepts Jesus and his miracles and other aspects of Christianity as part of its faith - with some differences in interpretation, and rejects other aspects.

[edit] Buddhist world

There has been much speculation regarding a possible connection between both the Buddha and the Christ, and between Buddhism and Christianity. Buddhism originated in India about 500 years before the Apostolic Age and the origins of Christianity.

[edit] Hindu world

The declaration Nostra Aetate officially established inter-religious dialogue between Catholics and Hindus. It has promoted common values between religions. There are over 17.3 million Catholics in India, which represents less than 2% of the total population and is the largest Christian Church within India. However, the Holy See has expressed concern with regards to religious violence in the state of Orissa, which is closely related to the ideology of Hindutva.

[edit] Secular world

Irreligion is an absence of religion, indifference to religion, and/or hostility to religion. Secularism, in one sense, may assert the right to be free from religious rule and teachings and freedom from the imposition of religion upon the people. In its most prominent form, secularism is critical of religious orthodoxy and asserts that religion impedes human progress because of its focus on superstition and dogma rather than on reason and the scientific method. Humanism refers to a philosophy centered around humankind. Much of Humanism's life stance upholds human reason, ethics, and justice, and rejects supernaturalism (Christian mythology).

Inga kommentarer:

Skicka en kommentar