Joseph Smith, Jr.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

Joseph Smith, Jr. (December 23, 1805 – June 27, 1844) was the founder and prophet of the Latter Day Saint movement. In the late 1820s, Smith announced that an angel had given him a set of golden plates engraved with a chronicle of ancient American peoples, which he had a unique gift to translate. In 1830, he published the resulting narratives as the Book of Mormon and founded the Church of Christ in western New York, claiming it to be a restoration of early Christianity.

Moving the church to Kirtland, Ohio in 1831, Smith attracted hundreds of converts, who were called Latter Day Saints. He sent some to Jackson County, Missouri to establish a city of Zion. In 1833, Missouri settlers expelled the Saints from Zion, and Smith's paramilitary expedition to recover the land was unsuccessful. Fleeing an arrest warrant in the aftermath of a Kirtland financial crisis, Smith joined his remaining followers in Far West, Missouri, but tensions escalated into violent conflicts with the old Missouri settlers. Believing the Saints to be in insurrection, the Missouri governor ordered their expulsion from Missouri, and Smith was imprisoned on capital charges.

After escaping state custody in 1839, Smith directed the conversion of a swampland into Nauvoo, Illinois, where he became both mayor and commander of a nearly autonomous militia. In 1843, he announced his candidacy for President of the United States. The following year, after the Nauvoo Expositor criticized his power and such new doctrines as plural marriage, Smith and the Nauvoo city council ordered the newspaper's destruction as a nuisance. In a futile attempt to check public outrage, Smith first declared martial law, then surrendered to the governor of Illinois. He was killed by a mob while awaiting trial in Carthage, Illinois.

Smith's followers consider him a prophet and have canonized as sacred texts some of his writings and revelations. His teachings include unique views of the nature of godhood, cosmology, family structures, political organization, and religious collectivism. His legacy includes several religious denominations, which collectively claim a growing membership of nearly 14 million worldwide.[1]

Life

Early years (1805–1827)

Joseph Smith, Jr. was born on December 23, 1805, in Sharon, Vermont to Joseph and Lucy Mack Smith, a working class couple.[2] Stricken with a crippling bone infection at age eight, he hobbled on crutches as a child.[3] In 1816-17, the Smith family moved west to the village of Palmyra in western New York,[4] and by July 1820 had obtained a mortgage for a 100-acre farm in the nearby town of Manchester,[5] an area that had fueled repeated religious revivals during this time known as the Second Great Awakening.[6]

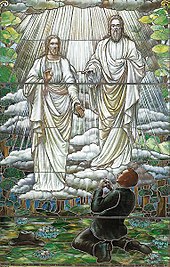

Smith and his family participated in the sectarian fervor and spiritual mystery of their day.[7] Although he may never have joined a church in his youth,[8] Joseph Smith participated in church classes[9] and read the Bible. With his family, he took part in religious folk magic,[10] a common practice but one condemned by many clergymen.[11] Like many people of that era,[12] both his parents and his maternal grandfather had mystical visions or dreams that they believed communicated messages from God.[13] Smith said that he had his own first vision in 1820, in which God told him his sins were forgiven[14] and, according to later accounts, that all churches were false.[15] Though generally unknown to early Latter Day Saints,[16] the vision story gained increasing theological importance within the Latter Day Saint movement beginning roughly a half century later.[17]

The Smith family supplemented its meager farm income by treasure-digging,[18] likewise relatively common in contemporary New England.[19] Joseph claimed an ability to use seer stones for locating lost items and buried treasure.[20] To do so, Smith would put a stone in a white stovepipe hat and would then see the required information in reflections given off by the stone.[21] In 1823, while praying for forgiveness from his "gratification of many appetites",[22] Smith said he was visited at night by an angel named Moroni, who revealed the location of a buried book of golden plates as well as other artifacts, including a breastplate and a set of silver spectacles with lenses composed of seer stones, which had been hidden in a hill named Cumorah near his home.[23] Smith said he attempted to remove the plates the next morning but was unsuccessful because the angel struck him down with supernatural force.[24]

During the next four years, Smith made annual visits to Cumorah, only to return without the plates because he claimed that he had not brought with him the "right person" required by the angel.[25] Meanwhile, Smith continued to travel western New York and Pennsylvania as a treasure hunter,[26] for which occupation he was tried in 1826 as a "disorderly person".[27] At one of his jobs, he met Emma Hale and eloped with her on January 18, 1827, because her parents disapproved of the match.[28] Claiming his stone told him that Emma was the key to obtaining the plates,[29] Smith went with her to the hill on September 22, 1827. This time, he said he retrieved the plates and placed them in a locked chest.[30] He said the angel commanded him not to show the plates to anyone else but to publish their translation, reputed to be the religious record of indigenous Americans.[31] Although Smith had left his treasure hunting company by then,[32] his former associates believed Smith had double-crossed them by taking for himself what they considered joint property.[33] They ransacked places where a competing treasure-seer said the plates were hidden,[34] and Smith soon realized that he could not accomplish the translation in Palmyra.[35]

Founding a new religion (1827–30)

In October 1827, Smith and his pregnant[36] wife moved from Palmyra to Harmony (now Oakland), Pennsylvania,[37] aided by money from their well-to-do neighbor Martin Harris.[38] Living near his disapproving in-laws,[39] Smith transcribed some of the "reformed Egyptian" characters he said were engraved on the plates and dictated their translations to his wife.[40]

Smith said that he used the "Urim and Thummim" for this early translation,[41] a term he used to refer to the silver spectacles found with the golden plates,[23] but no witnesses said they saw Smith using such spectacles.[42] Many witnesses did observe Smith translating using the same or similar method that he had previously used to find buried treasure: he would gaze at a seer stone in the bottom of his hat, excluding all light so that he could reportedly see the translation reflecting off the stone.[43] The plates themselves were not directly consulted.[44] Smith usually translated in full view of witnesses, but sometimes concealed the process by raising a curtain or dictating from another room.[45]

Smith may have considered giving up the translation because of opposition from his in-laws,[46] but in February 1828, Martin Harris arrived to spur him on[47] by taking the characters and their translations to a few prominent scholars.[48] Harris claimed that one of the scholars he visited, Charles Anthon, initially authenticated the characters and their translation, then recanted upon hearing that Smith had received the plates from an angel.[49] Although Anthon denied this,[50] Harris returned to Harmony in April 1828 motivated to act as Smith's scribe.[51]

Translation continued until mid-June 1828, until Harris began having doubts about the existence of the golden plates.[52] Harris importuned Smith to let him take the existing 116 pages of manuscript to Palmyra to show a few family members.[53] Harris then lost the manuscript—of which there was no copy—at about the same time as Smith's wife Emma gave birth to a stillborn son.[54] Smith said the angel had taken away the plates and he had lost his ability to translate[55] until September 22, 1828, when they were restored.[56]

Smith did not begin translating again in earnest until April 1829, when he met Oliver Cowdery, a teacher and dowser,[57] who now became Smith's scribe.[58] The two of them translated full time between April and early June 1829,[59] and then moved to Fayette, New York where they continued to work at the home of Cowdery's friend Peter Whitmer. When the translation spoke of an institutional church and a requirement for baptism, Smith and Cowdery had baptized each other,[60] years later claiming that John the Baptist had appeared and ordained them to a priesthood.[61] Translation was completed around July 1, 1829.[62] Knowing that potential converts to the planned church might find Smith's story of the plates incredible,[63] Smith asked a group of eleven witnesses, including Martin Harris and male members of the Whitmer and Smith families, to sign a statement testifying that they had seen the golden plates.[64] Secular scholars argue that the witnesses thought they saw the plates with their "spiritual eyes", or that Smith showed them something physical like fabricated tin plates, or that they signed the statement out of loyalty or under pressure from Smith.[65] According to Smith, the angel Moroni took back the plates after Smith was finished using them.[66]

The translation, known as the Book of Mormon, was published in Palmyra on March 26, 1830 by printer E. B. Grandin.[67] Martin Harris financed the publication by mortgaging his farm.[68] Soon thereafter on April 6, 1830, Smith and his followers formally organized the Church of Christ,[69] and small branches were established in Palmyra, Fayette, and Colesville, New York.[70] The Book of Mormon brought Smith regional notoriety,[71] but also strong opposition by those who remembered Smith's money-digging and his 1826 trial near Colesville.[72] Soon after Smith reportedly performed an exorcism in Colesville,[73] he was again tried as a disorderly person but was acquitted.[74] Even so, Smith and Cowdery had to flee Colesville to escape a gathering mob. Probably referring to this period of flight, Smith told years later of hearing the voices of Peter, James, and John who he said gave Smith and Cowdery an apostolic authority.[75]

When Oliver Cowdery and other church members attempted to exercise independent authority[76]—as when Book of Mormon witness Orson Hyde used his seer stone to locate the American New Jerusalem prophesied by the Book of Mormon[77]—Smith responded by establishing himself as the sole prophet.[78] Smith disputed Hyde's location for the New Jerusalem,[79] but dispatched Cowdery to lead a mission to Missouri to find its true location[80] and to proselytize the Native Americans.[81] Smith also dictated a lost "Book of Enoch", telling how the Biblical Enoch had established a city of Zion of such civic goodness that God had taken it to heaven.[82]

On their way to Missouri, Cowdery's party passed through the Kirtland, Ohio area and converted Sidney Rigdon and over a hundred members of his Disciples of Christ congregation,[83] more than doubling the size of the church.[84] Rigdon visited New York and quickly became second in command of the church,[85] to the discomfort of Smith's earlier followers.[86] In the face of acute and growing opposition in New York, Smith announced that Kirtland was the "eastern boundary" of the New Jerusalem,[87] and that the Saints must gather there.[88]

Life in Ohio (1831–38)

When Smith moved to Kirtland, Ohio in January 1831,[89] his first task[90] was to bring the Ohio congregation within his own religious authority[91] by quashing the new converts' exuberant exhibition of spiritual gifts.[92] Rigdon's congregation of converts included a prophetess that Smith declared to be of the devil.[93] Prior to conversion, the congregation had also been practicing a form of Christian communism, and Smith adopted a communal system within his own church, calling it the United Order of Enoch.[94] At Rigdon's suggestion,[95] Smith began a revision of the Bible in April 1831,[96] on which he worked sporadically until its completion in 1833.[97] Rectifying what Rigdon perceived as a defect in Smith's church,[98] Smith promised the church's elders that in Kirtland they would receive an endowment of heavenly power.[99] Therefore, in the church's June 1831 general conference,[100] he introduced the greater authority of a High ("Melchizedek") Priesthood to the church hierarchy[101]

The church grew as new converts poured into Kirtland.[102] By the summer of 1835, there were fifteen hundred to two thousand Mormons in the vicinity of Kirtland[103] expecting Smith to lead them shortly to the Millennial kingdom.[104] Though Oliver Cowdery's mission to the Indians was a failure,[105] he sent word he had found the site for the New Jerusalem in Jackson County, Missouri.[106] After he visited there in July 1831, Smith agreed and pronounced the county's rugged outpost[107] Independence to be the "center place" of Zion.[108] Rigdon, however, disapproved of the location, and for most of the 1830s, the church was divided between Ohio and Missouri.[109] Smith continued to live in Ohio but visited Missouri again in early 1832 in order to prevent a rebellion of prominent Saints, including Cowdery, who believed Zion was being neglected.[110] Smith's trip was hastened[111] by a mob of residents led by former Saints who were incensed over the United Order and Smith's political power.[112] The mob beat Smith and Rigdon unconscious and tarred and feathered them.[113]

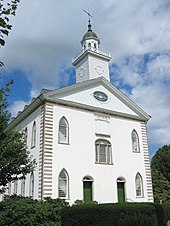

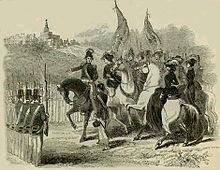

The old Jackson Countians resented the Mormon newcomers for various political and religious reasons.[114] Mob attacks began in July 1833,[115] but Smith advised the Mormons to patiently bear them[116] until a fourth attack, which would permit vengeance to be taken.[117] Nevertheless, once they began to defend themselves,[118] the Mormons were brutally expelled from the county.[119] Under authority of revelations directing Smith to lead the church like a modern Moses to redeem Zion by power[120] and avenge God's enemies,[121] he led to Missouri a paramilitary expedition, later called Zion's Camp.[122] When the camp found itself outnumbered, Smith retreated and produced a revelation explaining that the church was unworthy to redeem Zion in part because of the failure of the recently-disbanded[123] United Order.[124] Redemption of Zion would have to wait until after the elders of the church could receive another endowment of heavenly power,[125] this time in the Kirtland Temple[126] then under construction.[127]

Zion's Camp was a major failure[128] that stunned Smith for months[129] and resulted in a crisis in Kirtland.[130] But Zion's Camp also led to a transformation in Mormon leadership and culture.[131] Just before Zion's Camp left Kirtland, Smith disbanded the United Order[132] and changed the name of the church to "Church of Latter Day Saints".[133] After the Camp returned, Smith drew heavily from its participants to establish five governing bodies in the church, all of equal authority to check one another.[134] He also produced fewer revelations, relying more heavily on the authority of his own teaching,[135] and he altered and expanded many of the previous revelations to reflect recent changes in theology and practice, publishing them as the Doctrine and Covenants.[136] Smith also "translated" a papyrus obtained from a traveling mummy show, later published as the Book of Abraham.[137] The Saints built the Kirtland Temple at great cost,[138] and at the temple's dedication in March 1836, they participated in the prophesied endowment, a scene of visions, angelic visitations, prophesying, speaking and singing in tongues, and other spiritual experiences.[139] During the period, 1834–1837, Smith was at relative peace with the world.[140]

Nevertheless, after the dedication of the Kirtland temple, Smith's life "descended into a tangle of intrigue and conflict"[141] when, in late 1837, a series of internal disputes led to the collapse of the Kirtland Mormon community.[142] Since 1835, the church had publicly denied accusations that members were practicing polygamy,[143] but behind the scenes, a rift developed between Smith and Oliver Cowdery over the issue.[144] Smith had by some accounts been teaching a polygamy doctrine as early as 1831.[145] Some time after 1830 when the adolescent Fanny Alger started working as a serving girl in the Smith household, Smith entered a relationship with her,[146] and by 1833 he may have married her.[147] Cowdery, one of the few who knew about this relationship, called it a "dirty, nasty, filthy affair,"[148] a characterization Smith rejected.[149]

Even more troubling was Kirtland's financial state. Building the temple left the church deeply in debt, and Smith was hounded by creditors.[150] When Smith heard about treasure hidden in Salem, Massachusetts, he traveled there to search for it after receiving a revelation that God had "much treasure in this city"[151] and that Smith would be given power to pay his debts.[152] After a month, he returned empty-handed.[153] Smith then turned to wildcat banking, establishing the Kirtland Safety Society in January 1837, which issued bank notes capitalized in part by real estate.[154] Relying on a revelation, Smith invested heavily in the notes[155] and encouraged the Saints to buy them as a religious duty.[156] The bank failed within a month.[157] As a result, the Kirtland Saints suffered intense pressure from debt collectors and severe price volatility.[158] Smith was held responsible for the failure, and there were widespread defections from the church,[159] including many of Smith's closest advisers.[160] After a warrant was issued for Smith's arrest on a charge of banking fraud, Smith and Rigdon fled Kirtland for Missouri on the night of January 12, 1838.[161]

Life in Missouri (1838–39)

After leaving Jackson County, the Saints in Missouri established the town of Far West. Smith's plans to redeem Zion in Jackson County had lapsed by 1838,[162] and after Smith and Rigdon arrived in Missouri, Far West became the new Mormon "Zion."[163] In Missouri, the church also received a new name: the "Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints",[164] and construction began on a new temple.[165] Soon after Smith and Rigdon arrived at Far West, hundreds of disaffected Saints in Kirtland, suddenly realizing "the enormity of their loss," followed them to Missouri.[166] But Smith was unable to reconcile with many of oldest and most prominent leaders of the church, and he purged those critics who had not yet resigned.[167]

Though Smith hated violence, his experiences led him to believe that his faith's survival required greater militancy against anti-Mormons and Mormon traitors.[168] With his knowledge and at least partial approval,[169] recent convert Sampson Avard formed a covert organization called the Danites[170] to intimidate Mormon dissenters and oppose anti-Mormon militia units.[171] Sidney Rigdon was working to restore the United Order, but lawsuits by Oliver Cowdery and other dissenters threatened that plan.[172] After Rigdon's "Salt Sermon" ordered Mormons to "trample [the dissenters] into the earth",[173] the Danites expelled these dissenters from the county[174] with Smith's approval.[175] In a keynote speech at the town's Fourth of July celebration, Rigdon issued similar threats against non-Mormons, promising a "war of extermination" should Mormons be attacked.[176] After Rigdon's oration, Smith shouted "Hosannah!"[177] and allowed the speech to be published as a pamphlet.[178]

Rigdon's July 4 oration produced a flood of anti-Mormon rhetoric in Missouri newspapers and stump speeches during the political campaign leading up to the 6 August 1838 Missouri elections.[179] In Daviess County, where Mormon influence was increasing because of their new settlement of Adam-ondi-Ahman,[180] this election descended into violence when non-Mormons sought to prevent Mormons from voting. Although there were no immediate deaths,[181] the election scuffles initiated the Mormon War of 1838,[182] which quickly escalated as non-Mormon vigilantes raided and burned Mormon farms[183]. Meanwhile, under Smith's general oversight and command,[184] the Danites and other Mormon forces pillaged non-Mormon towns.[185] Before a cheering crowd of Saints, Smith declared that should there be non-Mormon attacks, Mormons would establish their "religion by the sword" and that he would be "a second Mohammed."[186] His angry rhetoric possibly stirred up greater militancy among Mormons than he intended.[187] When Mormons attacked the Missouri state militia at the Battle of Crooked River,[188] Governor Boggs ordered that the Mormons be "exterminated or driven from the state."[189] Before word of this order got out, non-Mormons vigilantes surprised and killed about 40 Mormons, including children, in the Haun's Mill massacre, effectively ending the war.[190]

On November 1, 1838, the Saints surrendered to 2,500 state troops, and agreed to forfeit their property and leave the state.[191] Smith was court-martialed and nearly executed for treason, but militiaman Alexander Doniphan, who was also the Saints' attorney, probably saved Smith's life by insisting that he was a civilian.[192] Smith was then sent to a state court for a preliminary hearing,[193] where several of his former allies, including Danite commander Sampson Avard, turned state's evidence.[194] Smith and five others, including Rigdon, were charged with "overt acts of treason,"[193] and transferred to the jail at Liberty, Missouri to await trial.[195]

Smith's months in prison with Rigdon strained their relationship,[196] and Brigham Young rose in prominence as Smith's defender.[197] Under Young's leadership, about 14,000 Saints[198] made their way to Illinois and searched for land to purchase.[199] Smith bid his time writing contemplative statements directed mainly to Mormons.[200] He did not deny responsibility for the Danites, but he said he had been ignorant of Avard's extreme militancy.[201] Though it had not been an issue in his preliminary hearing, he denied rumors of polygamy,[202] as he quietly planned how to reveal the principle to his followers.[203] Many Saints now considered Smith a fallen prophet, but he assured them he still had the heavenly keys.[204] He directed the Saints to collect and publish all their stories of persecution, and to moderate their antagonism to non-Mormons.[205]

Smith and his companions tried to escape at least twice during their four-month imprisonment,[206] but on April 6, 1839, on their way to a different jail after their grand jury hearing, they succeeded by bribing the sheriff.[207]

Life in Nauvoo, Illinois (1839–44)

The Mormon expulsion was an embarrassment to Missouri,[208] and Illinois was happy to welcome the refugees[209] who gathered along the banks of the Mississippi.[210] Smith purchased high-priced swampy woodland in the hamlet of Commerce[211] and urged his followers to move there.[212] Promoting the image of the Saints as an oppressed minority,[213] he unsuccessfully petitioned the federal government for help in obtaining reparations.[214] During a malaria epidemic, Smith anointed the suffering with oil and blessed them;[215]but he also sent off the ailing Brigham Young and other members of the Quorum of the Twelve to missions in Europe.[216] These missionaries found many willing converts in Great Britain, often factory workers, poor even by the standards of American Saints.[217]

The religion also attracted a few wealthy and influential converts, including John C. Bennett, M.D., the Illinois quartermaster general.[218] Bennett used his connections in the Illinois legislature to obtain an unusually liberal charter for the new city,[219] which Smith named "Nauvoo" (Hebrew נָאווּ, meaning "to be beautiful").[220] The charter granted the city virtual autonomy, authorized a university, and granted Nauvoo habeus corpus power—which saved Smith's life by allowing him to fend off extradition to Missouri[221] from which he was still a fugitive.[222] The charter also authorized the Nauvoo Legion an autonomous militia[223] with actions limited only by state and federal constitutions.[224] "Lieutenant General" Smith and "Major General" Bennett became its commanders,[225] thereby controlling by far the largest body of armed men in Illinois.[226] Smith, who was often a poor judge of character,[227] made Bennett Assistant President of the church,[228] and Bennett was elected Nauvoo's first mayor.[229] Though Mormon general authorities controlled Nauvoo's civil government, the city promised an unusually liberal guarantee of religious freedom.[230]

The early Nauvoo years were a period of doctrinal innovation. Smith introduced baptism for the dead in 1840,[231] and in 1841, construction began on the Nauvoo Temple as a place for recovering lost ancient knowledge.[232] An 1841 revelation promised the restoration of the "fulness of the priesthood,"[233] and in May 1842, Smith inaugurated a revised endowment or "first anointing."[234] The endowment resembled rites of freemasonry that Smith had observed two months earlier when he had been initiated into the Nauvoo Masonic lodge. [235] At first the endowment was open only to men, who once initiated became part of the Anointed Quorum. For women, Smith introduced the Relief Society, a service club and sorority within which Smith predicted women would receive "the keys of the kingdom."[236] Smith also elaborated on his plan for a millennial kingdom, no longer envisioning the building of Zion in Nauvoo.[237] He now viewed Zion as encompassing all of North and South America,[238] all Mormon settlements being "stakes"[239] of Zion's metaphorical tent.[240] Zion also became became less a refuge from an impending Tribulation than a great building project.[241] In the summer of 1842, Smith revealed a plan to establish the millennial Kingdom of God, which would eventually establish theocratic rule over the whole earth.[242]

In April 1841, Smith secretly wed Louisa Beaman as a plural wife, and during the next two and a half years he may have married thirty additional women,[243] ten of whom were already married to other men.[244] and about a third of them teenagers, including two fourteen-year-old girls.[245] Meanwhile he publicly and repeatedly denied that he advocated polygamy.[246] Smith told his potential wives that marriage to him would ensure their spiritual exaltation.[247] Although Smith's first wife Emma may have known about some of these marriages, she almost certainly did not know the extent of Smith's polygamous activities.[248] Smith kept the doctrine of plural marriage secret except for potential wives and a few of his closest male associates,[249] including Bennett. Smith's plural relationships were preceded by a "priesthood marriage", which Smith believed legitimized the relationships and made them non-adulterous. Bennett, on the other hand, ignored even perfunctory ceremonies.[250] When embarrassing rumors of "spiritual wifery" got abroad, Smith forced Bennett's resignation as Nauvoo mayor. In retaliation, Bennett wrote "lurid exposés of life in Nauvoo."[251]

By mid-1842, popular opinion had turned against the Saints.[252] Thomas C. Sharp, editor of the Warsaw Signal became a sharp critic after Smith attacked the paper.[253] When Lilburn Boggs, the Governor of Missouri, was shot by an unknown assailant on May 6, 1842, many suspected Smith's involvement[254] because Smith had held Boggs responsible for the Missouri expulsion and the Haun's Mill massacre.[255] Evidence suggests that the shooter was Porter Rockwell, a former Danite and one of Smith's bodyguards.[256] Smith went into hiding, but he ultimately avoided extradition to Missouri because any involvement in the crime would have occurred in Illinois.[257] Rockwell was tried and acquitted.[258] In June 1843, Illinois Governor Thomas Ford issued an extradition writ against Smith, but Smith countered with a Nauvoo writ of habeus corpus.[259] Ford later wrote that this incident caused a majority of Illinois residents to favor expelling Mormons from Illinois.[260]

In 1843, Emma reluctantly allowed Smith to marry four women who had been living in the Smith household—two of whom Smith had already married without her knowledge.[261] Emma also participated with Smith in the first "sealing" ceremony, intended to bind their marriage for eternity.[262] However, Emma soon regretted her decision to accept plural marriage and forced the other wives from the household,[263] nagging Smith to abandon the practice.[264] In response, Smith dictated a revelation[265] declaring that if Emma refused to accept Smith's other wives, she would be "destroyed."[266] When Smith's brother Hyrum presented the revelation to Emma, she abused him.[267] Nevertheless, in the fall of 1843, after Smith allowed women to be initiated into the Anointed Quorum,[268] Emma participated with Smith in the first second anointing.[269] According to Smith, this ritual was the prophesied "fulness of the priesthood" in which participants were ordained "kings and priests of the Most High God" and thus fulfilled what Smith called "[a] perfect law of Theocracy."[270] The Anointed Quorum became Smith's advisory body for political matters.[271]

In December 1843, under the authority of the Anointed Quorum,[272] Smith petitioned Congress to make Nauvoo an independent territory with the right to call out federal troops in its defense.[273] Then, Smith announced his own third-party candidacy for President of the United States, suspending regular proselytizing[274] and sending out the Quorum of the Twelve and hundreds of other political missionaries.[275] In March 1844, following a dispute with a federal bureaucrat,[276] Smith organized the secret Council of Fifty[277] with authority to decide which national or state laws Mormons should obey.[278] The Council was also to select a site for a large Mormon settlement in Texas, California, or Oregon,[279] where Mormons could live under theocratic law beyond other governmental control.[280] In effect, the Council was a shadow world government,[281] a first step toward creating a global "theodemocracy."[282] One of the Council's first acts was to ordain Smith as king of this millennial monarchy.[283]

Death

By the spring of 1844, a rift had developed between Smith and a half dozen of his closest associates,[284] most notably his trusted counselor William Law and Robert Foster, a general of the Nauvoo Legion.[285] Law and Foster disagreed with Smith about how to manage Nauvoo's theocratic economy,[286] and both believed Smith had proposed marriage to their wives.[287] After the dissidents organized, and one of them was heard predicting an uprising in Nauvoo,[288] Smith excommunicated them on April 18, 1844.[289] The dissidents formed a competing church[290] and the following month procured grand jury indictments against Smith for polygamy and other crimes in Carthage, the county seat.[291] In response, Smith and his followers unleashed a barrage of defamation against the dissidents,[292] and in a public sermon, Smith vehemently denied he had more than one wife.[293] After the dissidents published a prospectus for a new newspaper that referred to Smith as a "self-constituted monarch,"[294] the Council of Fifty offered to reinstate Law, but he refused to return to the church unless it renounced polygamy.[295]

Therefore, on June 7, 1844, the dissidents published the first and only issue of the Nauvoo Expositor, calling for reform within the church.[296] The paper decried polygamy and Smith's new "doctrines of many Gods" (taught recently in his King Follet discourse)[297] and alluded to Smith's kingship,[298] promising to present evidence of its allegations in succeeding issues.[299] At a meeting of the Nauvoo city council, Smith again denied that the church was practicing polygamy.[300] On the theory that the paper threatened to bring the countryside down on the Mormons,[301] the council ordered the Nauvoo Legion to destroy the Expositor's printing press as a public nuisance.[302]

Smith failed to foresee that suppressing the paper would sooner incite riots than allowing it to continue publishing.[303] Destruction of the newspaper provoked a strident call to arms by Thomas C. Sharp, editor of the Warsaw Signal.[304] Fearing an uprising, Smith mobilized the Nauvoo Legion on June 18 and declared martial law. Carthage responded by mobilizing its small detachment of the state militia, and Illinois Governor Thomas Ford appeared, threatening to raise a larger militia unless Smith and the Nauvoo city council surrendered themselves.[305] After instructing his clerk to hide or destroy the minutes of the Council of Fifty and ordering the Anointed Quorum to burn their temple garments,[306] Smith fled across the Mississippi River. Nevertheless, under pressure from Emma and other Saints, he returned and surrendered to Ford. On June 23, Smith and his brother Hyrum were taken to Carthage to stand trial for inciting a riot.[307] Once the Smiths were in custody, the charges were increased to treason against Illinois.

Smith and Hyrum were held in Carthage Jail.[308] On the morning of 27 June 1844, Smith sent a letter ordering the Nauvoo Legion to attack Carthage and free him, but the acting commander quietly disobeyed the order.[309] Later that day, an armed group with blackened faces stormed the jail and killed Hyrum instantly with a shot to the face.[310] Smith fought back with a pepper-box pistol that had been smuggled into the prison[311] but was shot while jumping from a window, then shot and killed as he lay on the ground.[312] Smith was buried in Nauvoo.[313] Five men were tried for his murder; all were acquitted.[314]

Distinctive views and teachings

Cosmology and theology

Smith was a materialist,[315] teaching that all spirit was material but composed of matter so fine that it was invisible to all but the purest mortal eyes.[316] Matter, in Smith's view, could neither be created nor destroyed;[317] the creation involved only the reorganization of existing matter.[318] Like matter, "intelligence" was co-eternal with God, and human spirits had been drawn from a pre-existent pool of eternal intelligences.[319] Nevertheless, spirits were incapable of experiencing a "fulness of joy" unless joined with corporeal bodies.[320] Embodiment, therefore, was the purpose of earth life.[321] The work and glory of God, the supreme intelligence,[322] was to create worlds across the cosmos where inferior intelligences could be embodied.[323]

Though Smith at first taught that God the Father was a spirit,[324] he eventually viewed God as an advanced and glorified man,[325] embodied within time and space[326] with a throne situated near a star or planet named Kolob and measuring time at the rate of a thousand years per Kolob day.[327] Both God the Father and Jesus had glorified bodies and were distinct beings. (The Holy Spirit was also a distinct being but did not have a body.) Through the gradual acquisition of knowledge,[328] and being sealed to one's salvation within the "New and Everlasting Covenant" that included celestial marriage, Smith taught that humans may become co-equals to God.[329] The ability for humans to progress to godhood implied a vast hierarchy of gods.[330] Each of these gods, in turn, would rule a kingdom of yet inferior intelligences, and so forth in an eternal hierarchy.[331]

The opportunity to achieve godhood extended to all humanity; those who died with no opportunity to accept Latter Day Saint theology could achieve godhood by accepting its benefit in the afterlife through baptism for the dead.[332] Children who died in their innocence were guaranteed to rise at the resurrection and rule as gods without maturing to adulthood.[333] Apart from those who committed the eternal sin, Smith taught that even the wicked and disbelieving would eventually achieve a degree of glory in the afterlife;[334]although they, as well as Mormons outside the "New and Everlasting Covenant," would serve those who had achieved godhood.[335]

Religious authority and ritual

A Christian primitivist, Smith viewed his original Church of Christ as a restoration of Early Christianity. In the beginning, Smith's church was established on the authority of religious experience and Smith's own charisma.[336] At first, the church had little sense of hierarchy, and Smith was only one of many potential prophets.[337] In succeeding years, Smith established himself as sole prophet of the church, and by 1835 he had organized a hierarchy with five co-equal governing bodies, [338] and three types of priesthood: Melchizedek, Aaronic, and Patriarchal.[339] As unfolded by Smith in the mid-1830s, these priesthoods derived their authority from angelic visitations or lineage.[340]

Beginning with the institution of the Melchizedek or High Priesthood in 1831, which Smith viewed as an "endowment" of heavenly power, Smith periodically introduced other Endowments until he elaborated the Nauvoo Endowment in 1842, which contains symbolism similar to freemasonry.[341] Smith thought these endowments were best performed in temples. Also associated with the High Priesthood were the sealing powers of Elijah, which included the power to seal Mormons to their godhood and exaltation,[342] the key to baptism for the dead,[343] and the mechanism whereby priesthood marriages could become eternal.[344] The most important ritual of the sealing power, which Smith called the "fullness of the priesthood," was the second anointing, which sealed couples to their eternal godhood and virtually guaranteed their salvation.

Smith also extended his authority to church members' economic lives. For instance, he tried to implement a form of religious communism, called the United Order, requiring Saints to consecrate all their property to the church. After this system proved a conspicuous failure, he instituted a tithing system to support the church.[345]

Theology of family

Smith gradually unfolded a theology of family relations called the "New and Everlasting Covenant"[346] that superseded all earthly bonds.[347] Smith taught that outside the Covenant, marriages were simply matters of contract,[348] and Mormons outside the Covenant would be mere ministering angels to those within, who would be gods.[349] To fully enter the Covenant, a man and woman must participate in a "first anointing," a "sealing" ceremony, and a "second anointing."[350] When fully sealed into the Covenant, Smith said that no sin nor blasphemy (other than the eternal sin) could keep them from their "exaltation," that is their godhood in the afterlife.[351] According to Smith, only one person on earth at a time—in this case, Smith—could possess this power of sealing.[352]

Smith taught that the highest exaltation would be achieved through "plural marriage" (polygamy),[353] which was the ultimate manifestation of this New and Everlasting Covenant.[354] Plural marriage allowed an individual to transcend the angelic state and become a god[355] by gaining an "eternal increase" of posterity.[356] Smith taught and practiced this doctrine secretly but always publicly denied it.[357] Nevertheless, Smith taught that once he revealed the doctrine to anyone, failure to practice it would be to risk God's wrath.[358]

History and eschatology

Smith taught that during a Great Apostasy, the Bible had degenerated from its original inerrant form, and the "abominable church", led by Satan, had perverted true Christianity.[359] He viewed himself as the latter-day prophet who restored those lost truths via the Book of Mormon.[360]. He described the Book of Mormon as a literal "history of the origins of the Indians."[361] These "Lamanites" as Smith called them, were descendants of Israelite tribes who had received their pigmented skin as a curse for sinfulness.[362] Though Smith first identified Mormons as gentiles, after 1832 he taught that Mormons, too, were literal Israelites.[363]

Smith also claimed to have regained lost truths of sacred history through his revelations and revision of the Bible. For example, he taught that the Garden of Eden had been located in Jackson County, Missouri, that Adam had practiced baptism, that the descendants of Cain were "black," that Enoch had built a city that was taken to heaven, that Egypt was discovered by the daughter of Ham, that the descendants of Ham were denied the Patriarchal Priesthood, that Abraham had discovered astronomical truths by peering into a Urim and Thummim, that King David had been denied his godhood because of his sin, and that John the Apostle would walk the earth until the Second Coming of Jesus.

Looking to the future, Smith declared that he would be an instrument in fulfilling Nebuchadnezzar's statue vision in the Book of Daniel: that he was the stone that would destroy secular government, which he would then replace with a theocratic Kingdom of God.[364] Smith taught that this political kingdom would be multidenominational and "democratic" so long as the people chose wisely; but there would be no elections.[365] Though Smith was crowned king, Jesus would periodically appear during the Millennium as the ultimate ruler. Following a thousand years of peace, Judgment Day would be followed by a final resurrection, when all humanity would be assigned to one of three heavenly kingdoms.

Race, government, and public policy

Except for a pro-slavery essay published over his name in 1836,[366] Smith strongly opposed slavery.[367] In his 1844 presidential campaign, he advocated abolishing slavery by 1850 and compensating slaveholders.[368] He did not believe blacks to be genetically inferior to whites, although he opposed miscegenation.[369] Smith welcomed both freemen and slaves into his church,[370] but he opposed the baptism of slaves without permission of their masters.[371] Smith also ordained free black members into the priesthood.[372]

Smith strongly favored U.S. constitutional rights, which he believed had been inspired by God. However, he did not believe that these rights were always adequately protected by existing governmental structures. For instance, he thought the U.S. federal government ought to have greater power to enforce religious freedom and other rights. Although Smith believed democracy better than tyranny, he taught that a benevolent or theocratic monarchy was the ideal form of government.

On matters of public policy, Smith favored a strong central bank and high import tariffs to protect American business and agriculture. Smith disfavored imprisonment of convicts except for murder, preferring efforts to reform criminals through labor; and he also opposed courts martial for military deserters. He favored capital punishment but opposed hanging, [373] preferring execution by firing squad or beheading in order to "spill [the criminal's] blood on the ground, and let the smoke thereof ascend up to God."[374]

Ethics and morality

Smith introduced as revelations from God a number of behavioral guidelines for church members, among which was what he called the "Word of Wisdom." Smith recommended that Saints avoid liquor, wine (except sacramental wine), tobacco, meat (except in times of famine or cold weather), and "hot drinks."[375] But Smith did not always follow this counsel himself.[376]Smith's revelations treated sexual sins, including adultery, almost as seriously as murder;[377]

Smith taught that those who kept the laws of God had "no need to break the laws of the land,"[378] but this principle was not absolute. Smith also taught that an act wrong in one context might be right in another because "[w]hatever God requires is right, no matter what it is."[379] For instance, the Book of Mormon approved the killing of a man and appropriation of his property because the killer had been moved by the Holy Spirit.[380] Smith believed he might occasionally violate laws and ethical norms in order to serve what he perceived as a higher religious purpose.[381]

Legacy

Religious denominations

Smith's death led to schisms in the Latter Day Saint movement.[382] Smith had proposed several ways to choose his successor,[383] but while a prisoner in Carthage, it was too late to clarify his preference.[384] Smith's brother Hyrum, had he survived, would have had the strongest claim,[385] followed by Joseph's brother Samuel, who died mysteriously a month after his brothers.[386] Another brother, William, was unable to attract a sufficient following.[387] Smith's sons Joseph III and David also had claims, but Joseph III was too young and David was yet unborn.[388] The Council of Fifty had a theoretical claim to succession, but it was a secret organization.[389] Some of Smith's ordained successors, such as Oliver Cowdery and David Whitmer, had left the church.[390]

The two strongest succession candidates were Sidney Rigdon, the senior member of the First Presidency, and Brigham Young, senior member of the Quorum of the Twelve. Most of the Saints voted for Young,[391] who led his faction to the Utah Territory and incorporated The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, now with over 13 million members.[392] Rigdon's followers are known as Rigdonites.[393] Most of Smith's family and several Book of Mormon witnesses temporarily followed James J. Strang,[394] who based his claim on a forged letter of appointment,[395] but Strang's following largely dissipated after his assassination in 1856.[396] Other Saints followed Lyman Wight[397] and Alpheus Cutler.[398] Many members of these smaller groups, including most of Smith's family, eventually coalesced in 1860 under the leadership of Joseph Smith III and formed what is now known as the Community of Christ, which now has about 250,000 members. As of 2010[update], adherents of the denominations originating from Joseph Smith's teachings number approximately 14 million.

Family and descendants

Smith legally wed Emma Hale Smith in 1826. She gave birth to seven children, the first three of whom (a boy Alvin in 1828 and twins Thaddeus and Louisa on 30 April 1831) died shortly after birth. When the twins died, the Smiths adopted another set of twins[401] whose mother had just died in childbirth (Joseph, who died of measles in 1832, and Julia).[402] Joseph and Emma Smith had four sons who lived to maturity: Joseph Smith III (November 6, 1832), Frederick Granger Williams Smith (June 29, 1836), Alexander Hale Smith (June 2, 1838), and David Hyrum Smith (November 17, 1844, born after Joseph's death). As of 2010[update], DNA testing has provided no evidence that Smith fathered any children from women other than Emma.[403]

Throughout her life and on her deathbed, Emma Smith frequently denied that her husband had ever taken additional wives. Emma claimed that the very first time she ever became aware of a polygamy revelation being attributed to Joseph by Mormons was when she read about it in Orson Pratt's booklet The Seer in 1853.[404] Emma campaigned publicly against polygamy and also authorized and was the main signatory of a petition in Summer 1842, with a thousand female signatures, denying that Joseph was connected with polygamy,[405] and as president of the Ladies' Relief Society, Emma authorized publishing a certificate in October 1842 denouncing polygamy and denying her husband as its creator or participant.[406] Even when her sons Joseph III and Alexander presented her with specific written questions about polygamy, she continued to deny that their father had been a polygamist.[407]

After Smith's death, Emma Smith quickly became alienated from Brigham Young and the church leadership, largely over property matters as it was difficult to disentangle Smith's personal property from that of the church.[408] Her strong opposition to plural marriage "made her doubly troublesome."[409] When most Latter Day Saints moved west, she stayed in Nauvoo, married a non-Mormon,[410] and withdrew from religion until 1860, when she affiliated with what became the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (now known as Community of Christ), which was first headed by her son, Joseph Smith III. Emma never denied Joseph's prophetic gift or her belief in the Book of Mormon.

Inga kommentarer:

Skicka en kommentar